This body of work began in 2016, when I went to Cuba for the first time in search of my great-grandfather’s cinema, the Cine Canal. He owned and ran the Cine Canal from the early 1930’s up until the revolution in 1959, where it was taken over by the government and left abandoned.The work deals with my position within the Cuban diaspora, using fragments from the history of Cuban cinema as a lens through which to explore the traumas of revolution, exile, and the resulting postmemory of future generations.

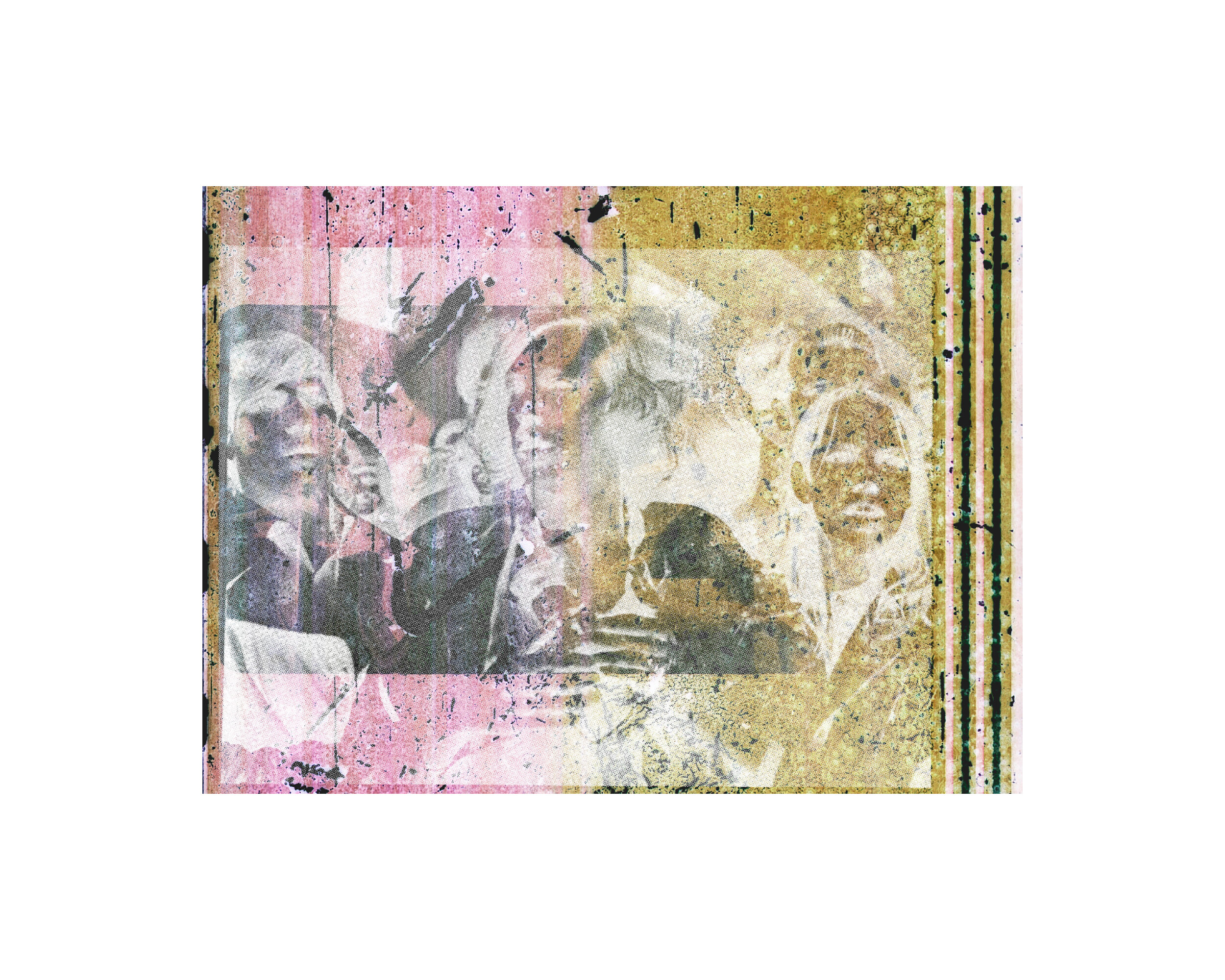

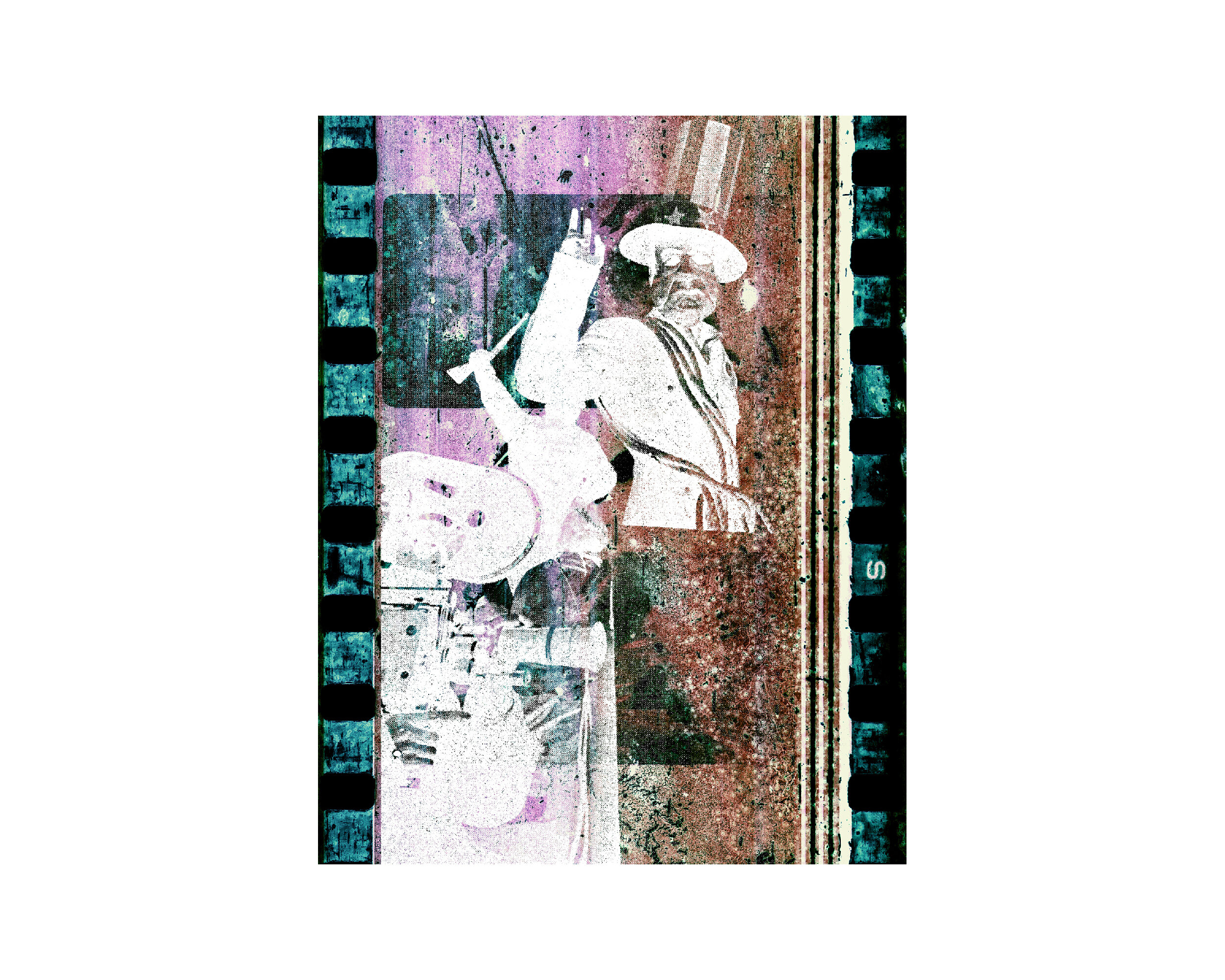

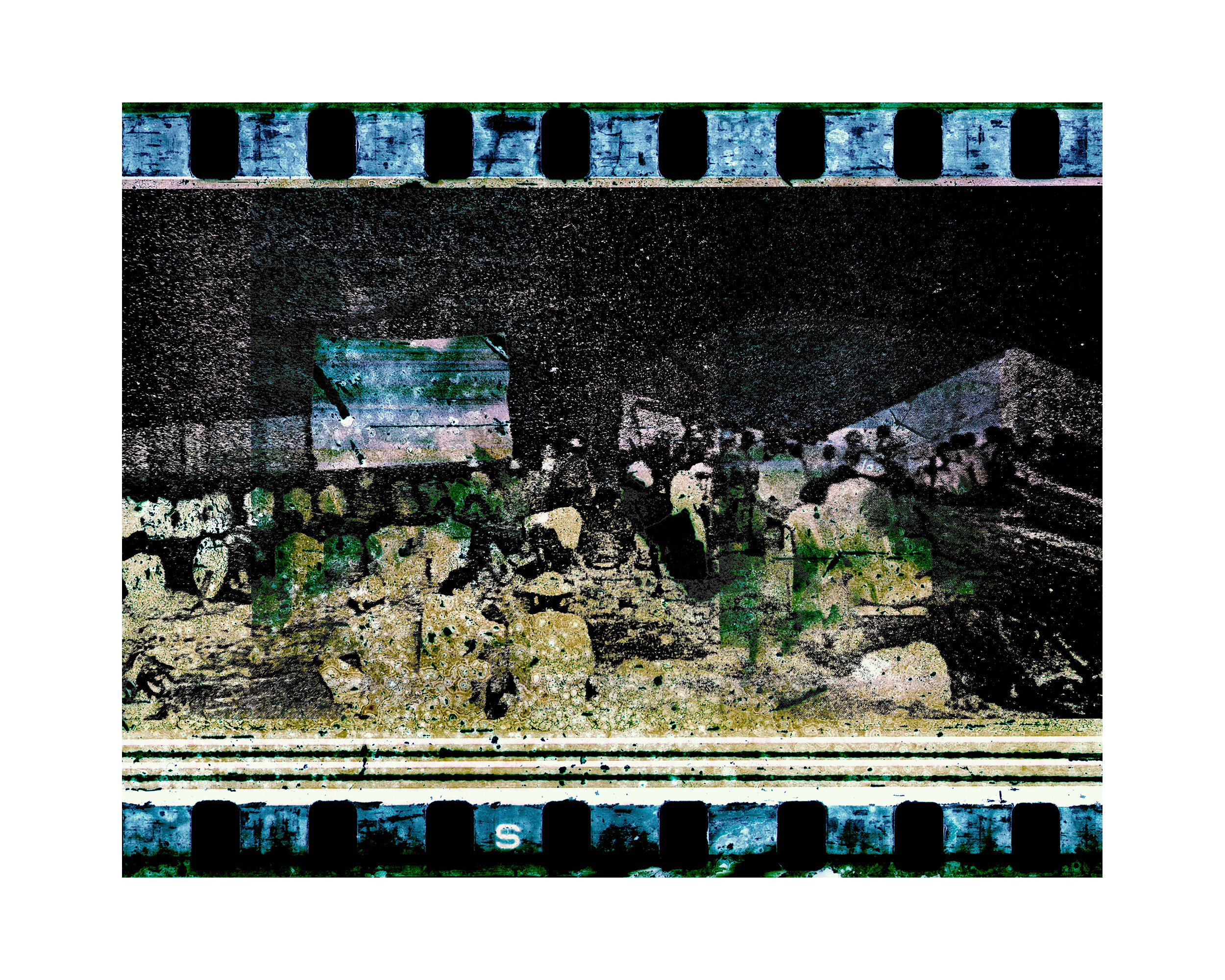

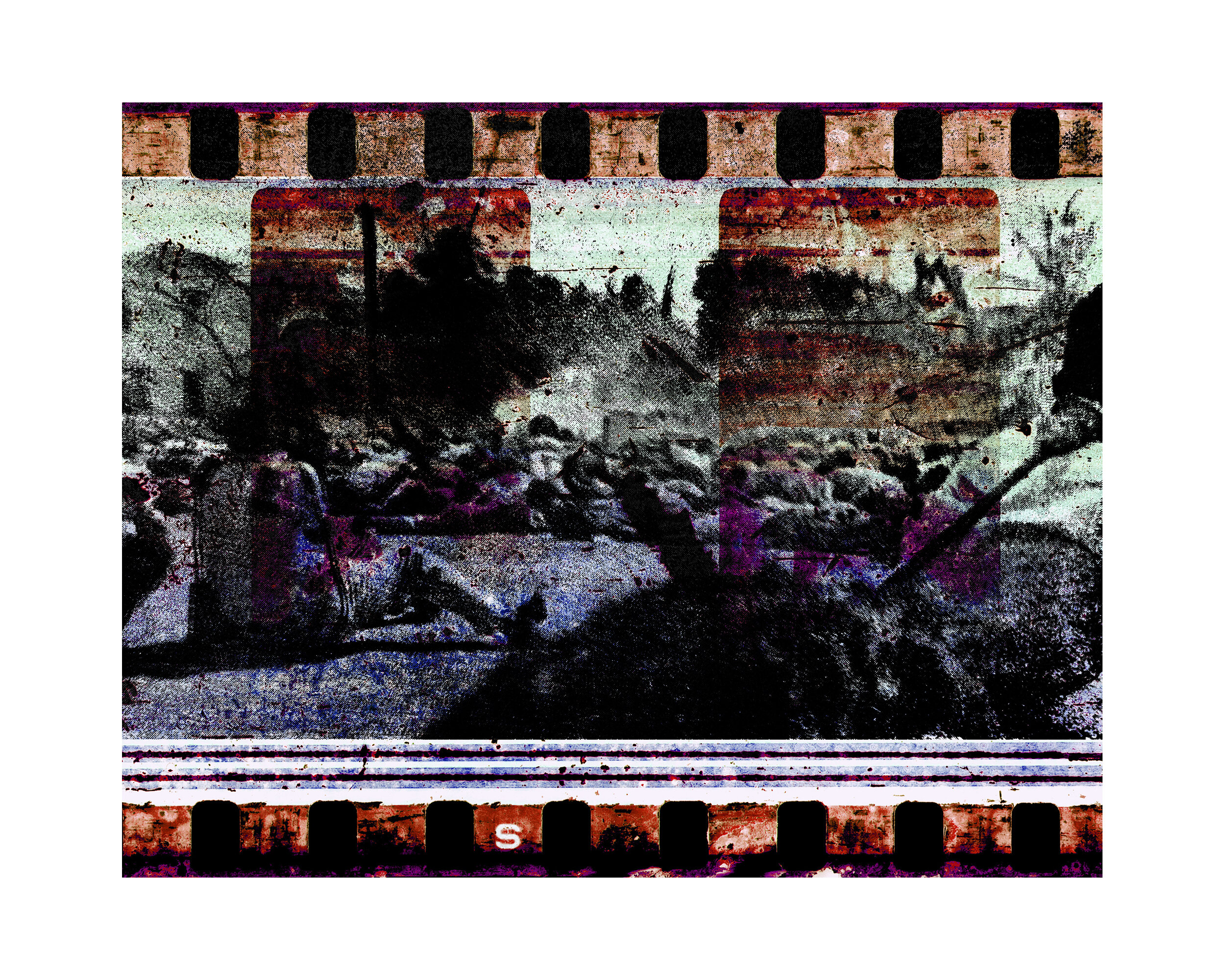

Enlarged onto chromogenic paper, decayed and scratched 35mm films found on the floor of the Cine Canal become colorful negative images with a palette reminiscent of Cuba’s architecture. Layered on top are images from within Cine Cubano 66/67, the highly influential magazine which first published Julio García Espinosa’s manifesto, Por un Cine Imperfecto. The manifesto champions a new cinema grounded in ‘imperfection’. It is a rejection of pristine, “reactionary” 35mm films in favor of smaller, more accessible formats like 8mm and 16mm, subscribing to an aesthetic of social realism. The contents of this magazine resulted in the abandonment of large cinemas including the Cine Canal, thus creating images directly on the film that are indexical of the slow decay of Communism. The layering results in a stark contrast between the fast violence of revolution – and the act of photographing – with the slow violence of time passed.

The contrast is, in that way, an overt conflict of ideologies and media. But it is also an ambiguous tension between fiction and non-fiction. The filmmakers that stand in line and aim their equipment could be a production team, or a firing squad. The woman: is she in character, or a corpse? And in totalitarian Cuba, are these cameras capturing objective truth, or objects for propaganda? Are the fatalities staged—are they true—and is there even a difference in the theatre of war?