W.A.S.P. (2020) is a product of my exploration of White, Anglo-Saxon Protestant domination in the U.S. South. It glares at the Old South’s nightmarish dimension: a dream of a lost, stolen paradise that, in contrast to the romance of “Gone With the Wind”, is actually nostalgia based on revisionist history, racial violence and a warped sense of the otherwise respectable values of heritage, honor, hospitality and home. And, by nature, it inspects my own discomfort and disorientation as a beneficiary of WASP supremacy.

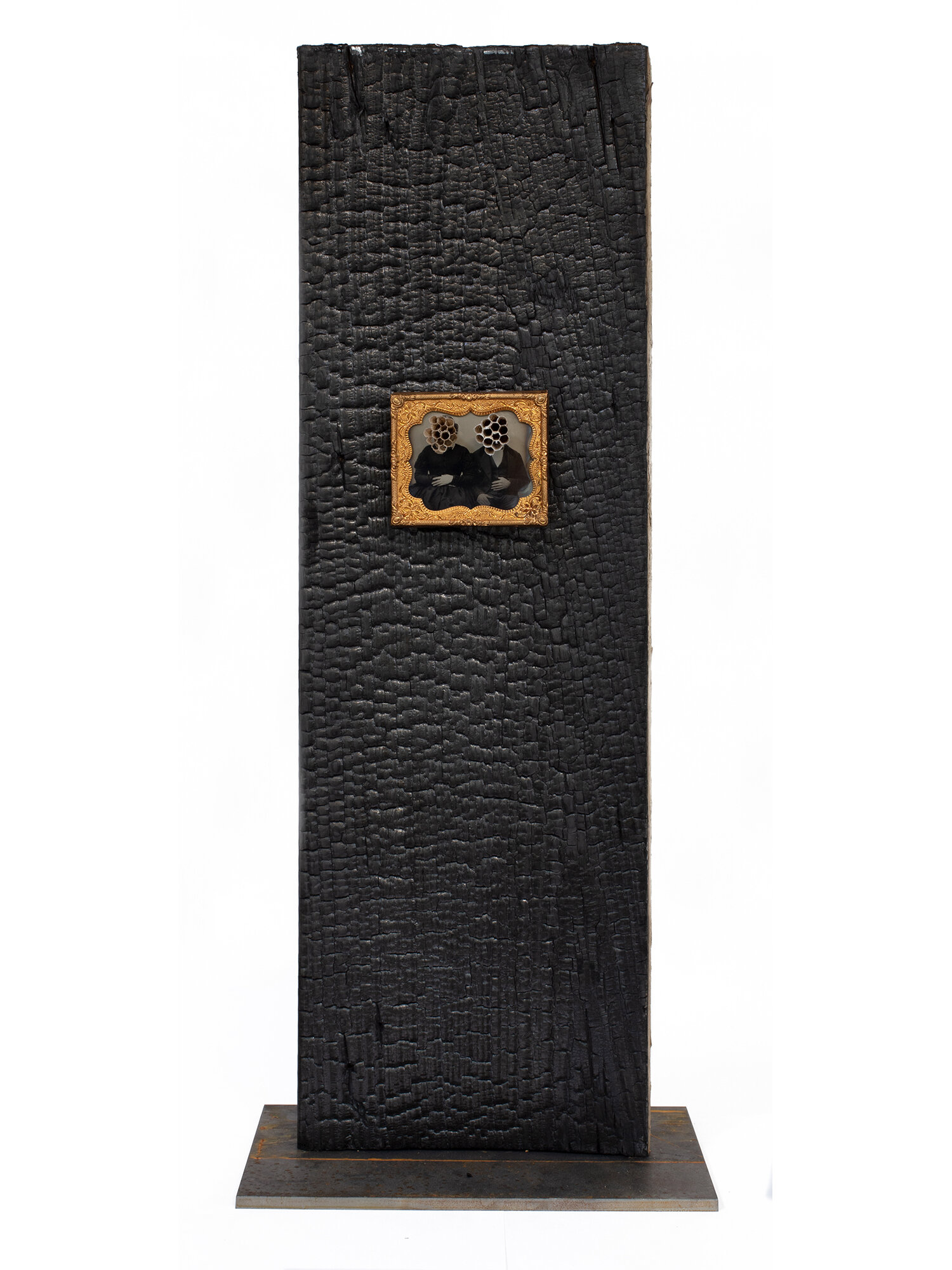

The daguerreotype portraits are from before the Civil War – a war which ravaged the South. The photographs are of Southern Belles and Gentlemen. Disturbingly, from the otherwise respectable mindset of heritage, honor, hospitality and home, the ideology of white supremacy sprouts out as a wasp’s nest. Wasps are rampant in the South; they are invasive, predatory insects. What if racism is like a wasp? Burrowing its nest into houses’ walls, and feeding off both sincere principles and other human beings to hatch a virulent sense of intolerance and supremacy?

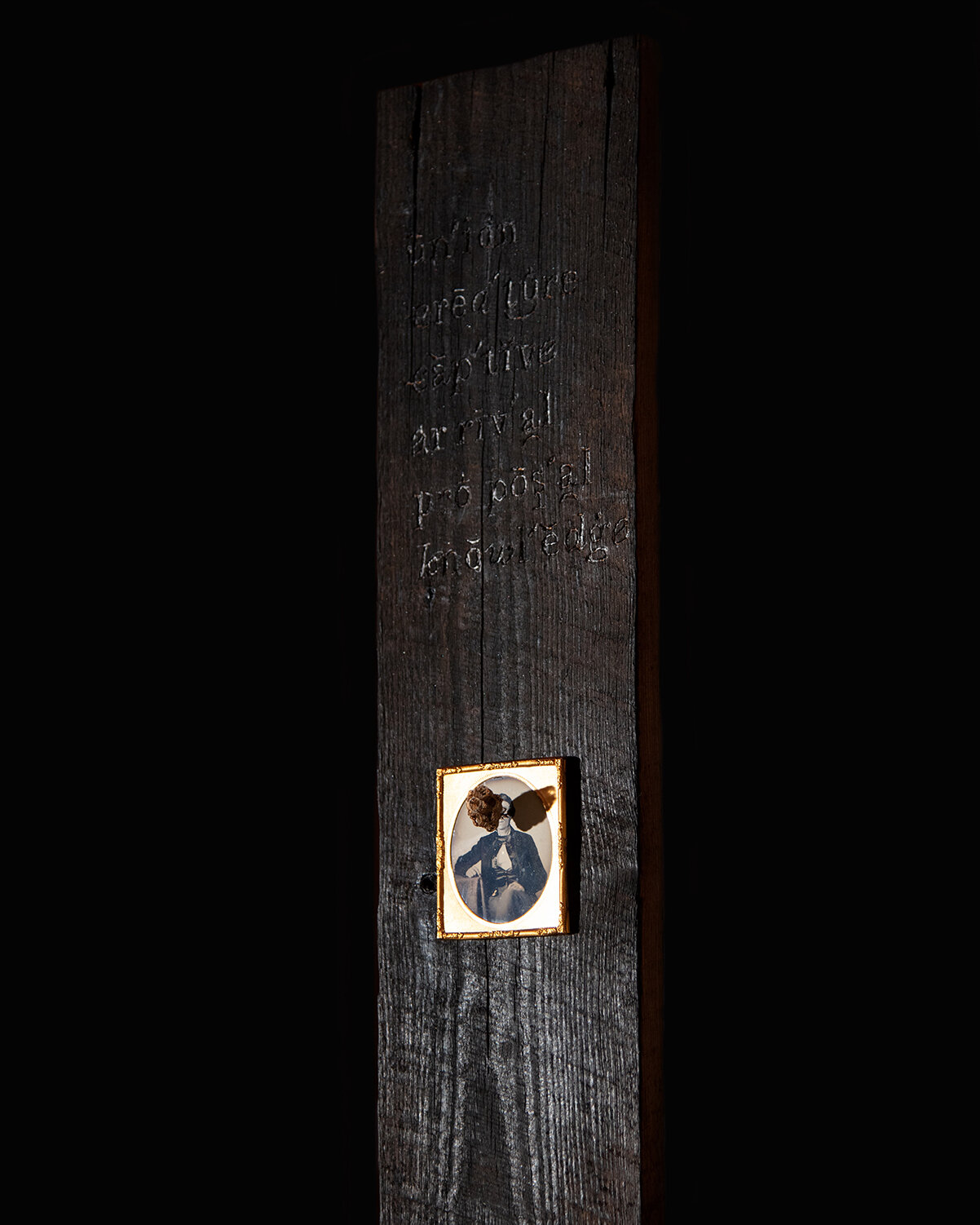

The boards which frame the ambrotypes are all from homes in rural Georgia. Each floorboard is a piece of Southern society’s greater structure. They are charred by fire in reference to the burning of Southern cities like Vicksburg and Atlanta after their defeat —secession had ended in the material destruction of the Old South. Yet the Old South as a dream did not die, rather, it mutated. After the war, the ground was fertile for fantasizing about the way things had been and the way they could have been had the South been left unharmed. There is also a nefarious dimension: the cracked surface of the burnt wood looks like blackened skin, and, just as many of the impoverished populations hit by the post-war Reconstruction Era were mostly of color, the planks are far larger than the photographs. It is a polemic of how collective amnesia and romanticism whitewash a brutal past to validate “white heritage.”

W.A.S.P. extends beyond the domestic space; it looks into education, too. The last daguerreotype is nailed to a school desk scribbled on by children in the ’10s and ’20s in a small-town classroom where students learned arithmetic, grammar, manners—and all the while underlain with a Southern understanding of the Birth of this Nation: a schizophrenic merger of Confederate nostalgia and pride in being American. Or, rather, being “truly” American: White, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant.